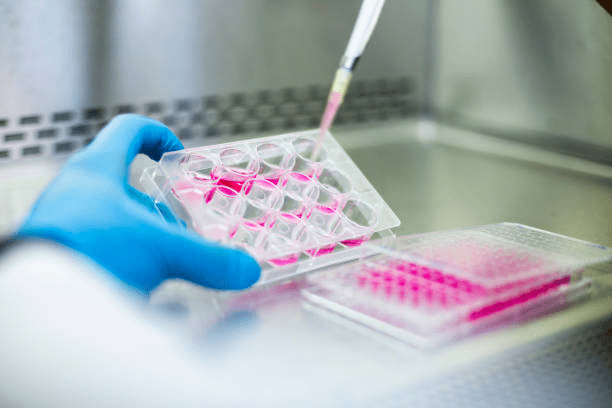

The centrifuge whirrs in the background as I click open the next raw data csv file, preparing to analyze another batch of flow cytometry data that a dismissed bioinformatician left behind. In the shared Box drive, there were scattered files, incomplete annotations, and months of hard work requiring resurrection. At sixteen, I found myself wondering, “What exactly am I doing here?” Or more specifically, “What are any of us high schoolers doing here?”

As I glance across the Georgetown Lombardi Cancer Center lab, I’ve noticed that the summer months have brought an influx of students like myself. We are teenagers excited by genuine scientific curiosity and a hunger for real-world experience. Without a doubt, our existing knowledge is enough to contribute meaningfully to cutting-edge research. However, the clear age difference and our lack of professional experience begs the question of whether we truly belong in these places populated by doctoral candidates and life-long researchers.

Resource Sink

Some researchers such as Terry McGlynn have expressed resistance to taking on high schoolers in their labs. In his blog, Dr. McGlynn reasons that the resources and time spent by his graduate students to train high schoolers takes away from real scientific progress. Additionally, he claims that “These students [who] want to join my lab are the kind that end up winning science fairs because of privileged access to university resources.”

Dr. McGlynn’s concerns are reasonable, especially during a time of intense funding cuts and uncertainty. Lab materials cost a fortune. With a reduced work force, work and time is spread thin across the existing researchers. However, in my experience, if the students have enough existing knowledge and a desire to learn, teaching them should not detract from the post-grads’ research. Furthermore, the blanket assumption that every high schooler is only seeking laboratory experience to get into a “fancy university” or that they had unfair advantages due to elite status is uncalled for. Many of us, myself included, are here because we are genuinely fascinated by the cutting-edge scientific advancements. We are not all products of privilege seeking another line on our resumes. In fact, in an era of funding cuts and reduced workforce, dismissing willing and capable hands simply because they happen to be young seems less like resource management and more like academic gatekeeping.

Unexpected Contributions

When I first entered the lab this summer, I expected to take ownership of and conduct my own research project using the lab’s space while contributing to the lab’s goals. Instead, I found myself inheriting an incomplete project from a departed bioinformatician that needed urgent work for upcoming paper publications. While I had initially expected to take home an independent project this summer, I now realize that the contribution I am making to a team mission is much more meaningful and valuable. Without my help, the papers that depend on this data might have remained in limbo for months longer, victims of funding cuts. Being an integral part of cutting-edge research is exhilarating. My work feels needed and important, and I am grateful to have been given this opportunity to contribute to real-world science.

Thoughts

So if high schoolers can contribute meaningfully to research (like myself and several of my friends), is the time and resources spent training them worth it? If our fresh ideas and questions sometimes illuminate perspectives that experienced researchers have overlooked, what does that say about the value of intellectual diversity in scientific settings? Or is it still wasteful to train researchers who will leave after a few months or years? Perhaps it is precisely this temporary nature that makes our contributions valuable as we are unburdened by the career pressures and institutional politics that sometimes constrain senior researchers?

As I return to my cytometry analysis, I realize that the answer to my question lies in high schoolers’ eagerness to participate in something larger than themselves, their intentions, and their capabilities. As long as we are helping progress science, that is our job, and age in itself should not be a limitation. While we may not have the years of specialized training and education of a PhD, we can contribute whatever knowledge and skills we do have.

Up Next!

Part 2 will be more about the lessons a high schooler can gain from a lab research opportunity while also considering the potential risks.

Leave a comment