Many people have heard of the famous HeLa cells that helped advance medical research, from the development of the polio vaccine to research on zero gravity and cancer, but the story behind these cells is what is most fascinating to me.

In general, a cell will die after a certain number of replications. Cancer cells, however, have mutations that enable them to multiply out of control. This makes cancer cells ideal for medical research. Yet not all cancer cells are good culture cells. Some require very specific conditions of culture medium. Remarkably, HeLa cells are able to double within 24 hours and are amenable to a wide variety of conditions, unlike other cancer cells.

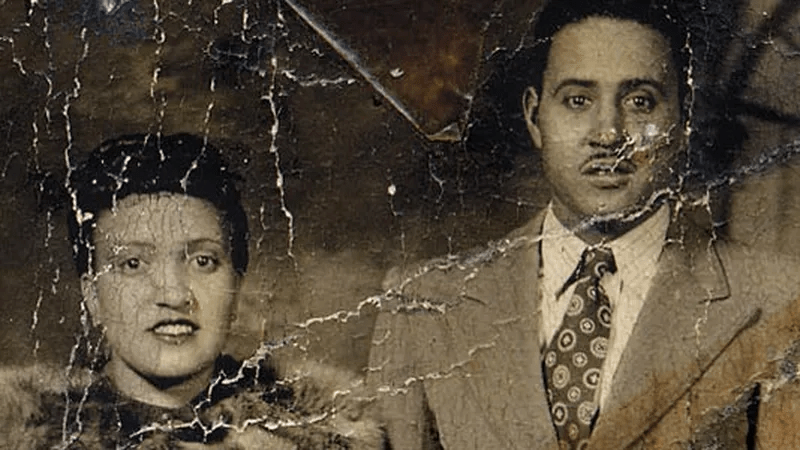

Sadly, Henrietta Lacks, the woman behind these extraordinary cells, known as HeLa cells, is virtually unknown. She was a poor black woman born in 1920 in Roanoke, Virginia. This was a time when racial and socio-economic disparities in the healthcare system were pervasive, and bioethics and consent in medicine were almost nonexistent, especially towards the black community. For instance, black people were used as human subjects in the Tuskegee syphilis study, and black children were abducted to be part of scientific experiments. In her 20s, Henrietta was diagnosed with cervical cancer. During her treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital, her cells were taken to grow in a lab without her consent. Guess what? These cells were the first to survive and thrive in conditions that would typically destroy other cells. This remarkable ability to replicate indefinitely in laboratory conditions allows scientists to conduct long-term experiments on human cells without needing to constantly obtain new samples.

Only 20 years after her death did Henrietta’s family learn of her cells’ “immortality” when scientists began using her husband and children to investigate HeLa. By then, HeLa cells have been widely distributed and used in scientific research in a multi-million-dollar industry. Her family never saw these profits. Her children were left wondering why they could not afford health care if their mother’s cells were so important to medicine.

The story of Henrietta Lacks and her cells has sparked discussions about bioethics of consent, privacy, and the rights of individuals in medical research, and whether we own what we are made of. I am glad that we now have laws that require informed consent for health care.

Leave a comment