If you are curious about how medicine evolved alongside scientific discoveries, the eerie and illuminating book The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine by Lindsay Fitzharris is a must-read. It takes you, the curious readers, on a journey to a nineteenth-century hospital where you feel like you are experiencing the gory sights, sounds, and smells of surgery firsthand. No details were spared.

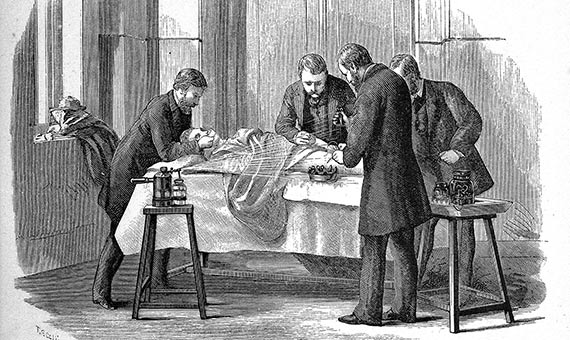

Two centuries ago, surgeons were practically more dignified butchers. Doctors believed that infections were caused by “animalcules” that spawned de novo (spontaneously). Little did they know that their bloodied, pus-covered saws unwiped after each surgery as well as the poorly ventilated hospital they worked in were the cause of these fatal infections. Because of the high mortality rates, doctors often refused to operate until the patient was close to death. But by then, the amputation procedure would probably kill the patient faster than their ailment. Even worse, these brutal procedures were performed without anesthesia until the mid-1800s! Screaming out in excruciating pain, patients had to be strapped down and chained to a bloody table. Thanks to the revolutionary surgeon Joseph Lister, we are no longer treated like this today.

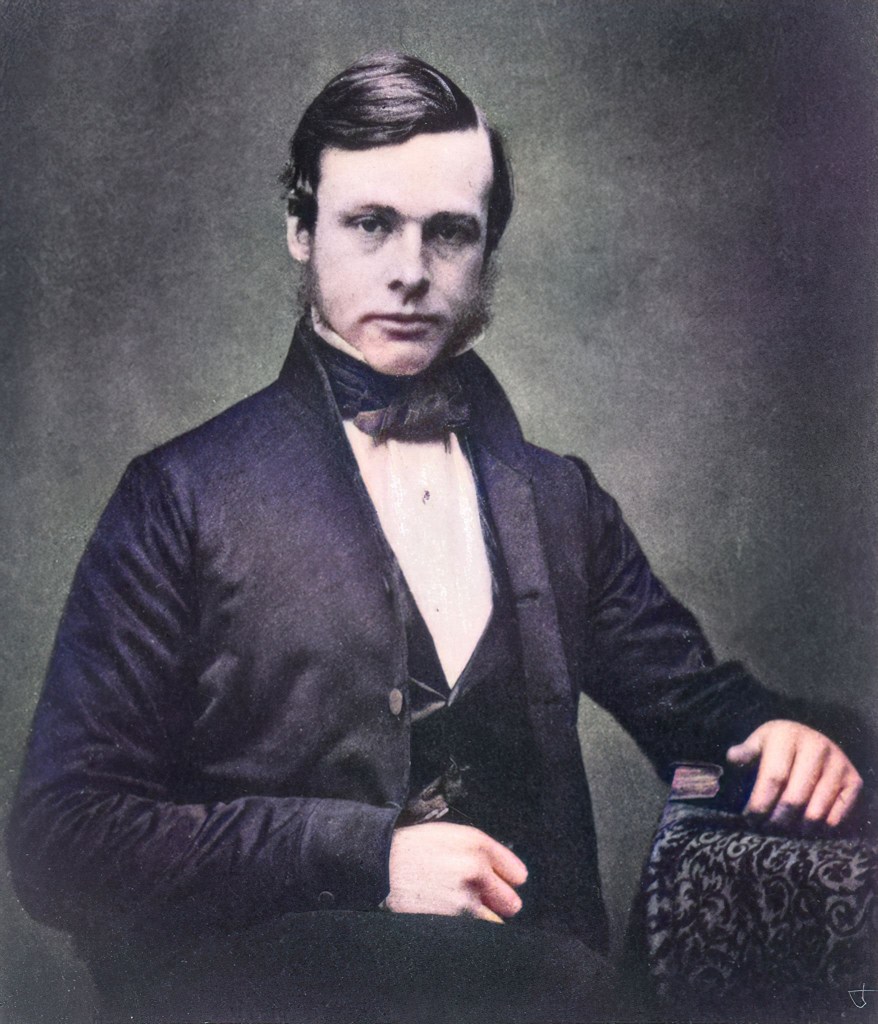

We might have heard of Louis Pasteur who was behind the scientific discovery of microbial fermentation. But it was Lister who applied that science to medicine, pioneered the prevention of infection from surgery, and spread his findings to the world. He found that thoroughly washing his hands, instruments, and the wound with diluted carbolic acid prevented infection. This astounding discovery led to infection and mortality rates plummeting in his wards.

Continuing to perfect his method of using carbolic acid, Lister shared his results with London, Germany, France, and the US. Gradually, more and more people became convinced of his treatment methods. While his specific antiseptic method is no longer used, his principle that microbes should never enter a wound remains the basis of modern medicine.

Now you know after whom Listerine, the mouthwash, was named for its antiseptic properties!

Leave a comment